Memories of Mandelay

- Steve Goodman

- Apr 25, 2024

- 9 min read

Updated: Apr 30, 2024

by Steve Goodman, founding executive director emeritus

This is the second in a series of guest blog posts written by EVC’s founding executive director emeritus, Steve Goodman, on EVC’s early years. Read the preceding blog post in this series here.

The group of students reviewed their storyboard one last time, then walked together down the school hallway, careful not to get tangled up in the various cables connecting the recording deck to their camera, microphone, headphones, and battery belt they were carrying. Another group of students took up their positions on “the set” as actors playing students smoking and drinking in the girls’ bathroom. Once the tape was rolling, the student playing the school’s dean kicked in the bathroom door and proceeded to bust the students inside.

This was a memorable day during the first video class I taught back in 1981 at Satellite Academy, a public high school on Manhattan’s Lower East Side. The film that the students were working on would come to be called “Memories of Mandelay.”

Satellite was designed for students who had been poorly served by New York City’s large traditional public schools. Students transferred to the alternative school for a range of academic, social-emotional, and in some cases, court-ordered reasons. When I met these students, most were struggling to graduate but happy to be going to high school in a small, more supportive environment. There were 18 students in the class that I was co-teaching with English teacher Liz Andersen.

DCTV, one of New York’s first community media organizations, loaned the class a black and white, reel-to-reel Portapak (a popular Sony video recording deck) and an editing deck, housed at the DCTV firehouse studio in Chinatown.

The community media movement was a little over a decade old. DCTV was part of a flourishing group of video collectives and centers in Lower Manhattan, including Global Village, Young Filmmakers, and Paper Tiger TV, among others. These organizations were hives of activity and provided free and low-cost access to video production and editing equipment, as well as training workshops. Media artists working at DCTV produced and screened work across numerous genres, including experimental video art, guerrilla TV, domestic and international documentary films, and news analysis shows.

The Lower East Side and East Village neighborhoods surrounding Satellite had become a vibrant scene for music, art, and video. Graffiti tags, street art, and murals were everywhere. The barking dogs and radiant baby figures of street artist and activist Keith Haring started appearing on buildings and subway stations throughout the neighborhood—he even came into Satellite and drew one of his pieces on a school blackboard. Another local street artist, Jean Michel-Basquiat (who attended City-as-School, where EVC now has its offices) would have his first solo show the next year. Many Satellite students were also street artists in their own right and were increasingly known for their tags and throw-ups, their raps, and their gravity-defying break-dancing. Some students came to school as walking art exhibitions, showing off their original colorful spray paintings on the backs of their denim jackets. (The twin plagues of crack and AIDS would soon come to ravage the art world, the community, and our school, as well. We would lose two beloved Satellite educators to AIDS, Stephen Shapiro and Steve Chevastick.)

“Memories of Mandelay” grew from the students’ own interests, questions, and experiences. First they brainstormed ideas and then co-created a plan for the project. This methodology became foundational to EVC’s teaching practices. The pedagogical approach became more widely known as “youth-centered” or “student-centered” with the growth of the youth development and small schools movements in the 1980s and 90s. Once EVC landed on it we would never waver from this principle.

The students’ initial brainstormed list of project ideas is a snapshot of what was on their minds at the time:

Atlanta murders of Black children

Problems of old people

Hidden talents of people

Hells Angels

Satellite students in group homes

Street performers – jugglers, magicians

Court systems

Rikers Island

Child Abuse

This list reflects a mix of what the students had experienced themselves—events in their families, communities, and neighborhoods—and topics they simply wanted to learn more about.

Once they generated this list, we set about the task of narrowing it down. I advised them that while some ideas were exciting and important, we had to consider their practicality since we only had six weeks to create our video. For instance, traveling to Atlanta, documenting the Hells Angels in their nearby clubhouse, or interviewing youth in Rikers Island presented significant logistical challenges, so those topics didn’t end up receiving many votes from the class. The idea to explore people’s hidden talents never developed into a film, but we did use it to inspire a practice session in which youth interviewed people in the streets.

I noted in my journal:

There was interest in the group homes project. But there was also resistance and I wasn’t quite sure why. They kept saying that no one would talk. No one would ever open up about all the bad things that went on. Finally I asked if anyone knew someone in a home or had been in one themselves. Two hands went up….

One student, Lisa, said that she had lived in a group home, and she knew of several such homes around the city. She also knew quite a few students who lived in homes now. We could interview some of these young residents, and some former residents, and we could also interview their families. When asked her reason for wanting to make a video on this subject, Lisa said, “To show how fucked up all institutions are!” Lisa’s own lived experience—her personal connection to these institutions and potentially to others who had lived in group homes—gave substance and authenticity to this project idea. That settled it: the students would focus their film on group homes.

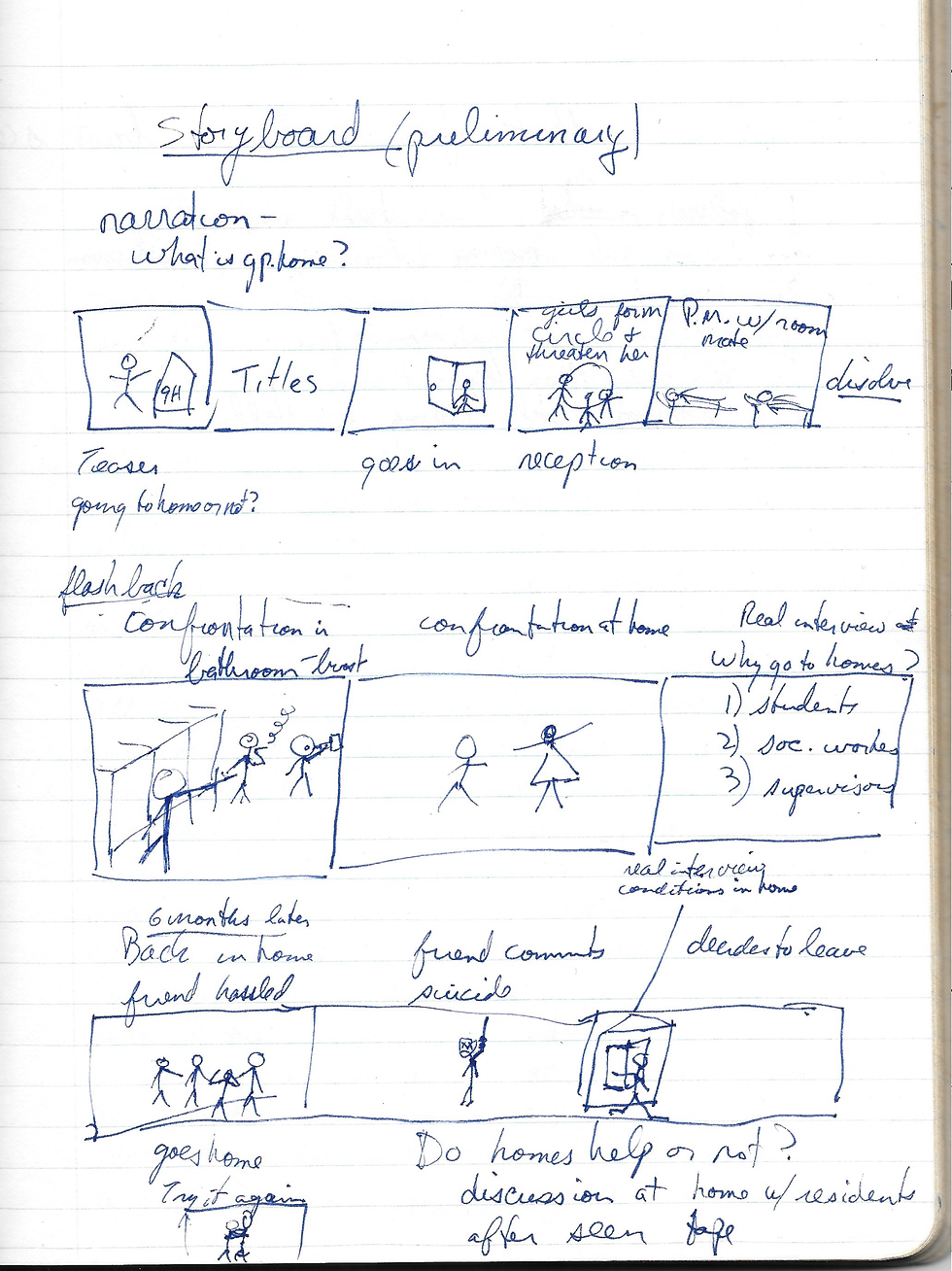

Next, we drew a storyboard, sketching out what the arc of the story might look like.

I prompted the group: How would we begin?

Well, the kid has to do something bad to be put there in the first place.

Like robbing a store? I suggested.

A student draws a stick figure holding a gun in the storyboard’s first panel.

No, they have to be on drugs and then steal to pay for the habit.

So panel one had the title: “Doing something bad.” What next? I asked.

They have to get caught. A bust scene!

Five minutes earlier, the students had said no one would ever talk about their experience. Now they were clearly speaking from, and of, their experiences as they contributed to the “fictional” story.

We continued building the story. They felt since it would be impossible to record a student “doing something bad,” they agreed to act out those scenes as kind of a flashback or reenactment showing how the student arrived in the group home. Then they would interview an actual student living in the group home and use this audio over the reenactment.

The idea of creating a non-fiction documentary began changing into what students imagined as more of a hybrid. They would dramatize a story of a composite character drawn from Lisa and other students’ real-life experiences. I noted:

…We thought of juxtaposing the acted-out scenes with the real ones. For example, an interview with a social worker cut next to the kids’ version. And then showing the tape of the kids in the home and taping their reaction to how real or unreal the tape’s depiction is.

In this way, we would expand the traditional roles of director and producer to include not just the youth making the video, but also the youth who were the video’s target audience. Inspired by Augusto Boal and Paulo Freire, the idea was for the youth audiences in the group home to critique, on camera, the reenactment, and compare it to their own reality. Brazilians Boal and Freire were a drama practitioner and an educator, respectively, whose widely influential books, Theatre of the Oppressed and Pedagogy of the Oppressed, described their drama and literacy theories and practices for empowering poor communities to become active participants in their liberation from oppression.

The next step would be for the youth in the group home to suggest how they would have made the reenactment differently and what other solutions they believed could be found to the challenges they shared in common. This approach, as I journaled, was about “breaking down the barrier between spectator and participant and push[ing] everyone into the arena as participant-producer.”

But I digress. I’ll rewind back to the action again. According to my notes:

The students really rose to the occasion. We acted out two scenes: the school bathroom bust and the confrontation with the mother….The group who was acting went to the bathroom armed with tobacco-filled joints, wine bottles (with water in them) and a radio. Lisa was to be the central figure, the girl who gets in trouble and goes to the home. Felicia was to play her mother who is called in to see her. And Marcus was the dean who busts the kids. Miguel held the light…. We began the scene over starting from before the dean kicked in the door. And this time the camera was facing the door…. Some shots of the kids drinking and smoking and partying were taken and then on the cue word “pass the joint” Marcus burst through onto the “set.” Once he entered the bathroom and the door closed behind him the kids were left alone to shoot the scene…. The scene ended after Lisa, caught drinking wine, refused to obey the dean’s orders and emptied the bottle into her mouth only to spit it out into his face. The camera clicked off and we went off to watch what was shot.

In the story, emotions escalated to a boiling point when Lisa’s mother, played by another student, arrived in the principal’s office. This was the last straw, and Lisa’s mother was sending her to a group home. The improvised argument between Lisa and her mother was very powerful and very real. When it was over, the staff and students who heard the commotion and now filled the office burst into applause. Everyone hugged.

Telling how Lisa ended up in a group home was the first part of the story. Showing what her life was like behind the closed doors of an institution was the next part. After calling group homes in New York City and Westchester, we finally found one that would allow in our student actors and camera crew.

The house mother welcomed us into the group home, and even acted in some of the scenes.

I wrote:

Today was another incredible shoot…. We actually went to the group home out in Queens…. The most marvelous part of the whole day was the interaction between the Satellite students and the home residents. At first the residents were timid; a bit overwhelmed … But as the story unfolded the residents participated more and more until finally they became an essential part of the story—especially in the group home scenes….

The climax of the story is when Lisa’s best friend in the group home overdoses on pills after being abused and bullied there. Lisa leaves and returns home to her mother.

The footage of “Memories of Mandelay” was logged and edited. We planned to use the tape to spark discussion among group home youth residents. But screening it at one near the school proved more difficult than expected. At first they told us that the dramatized suicide scene made it unsuitable for the youth to see. They finally agreed to show it to a handful of residents and a heated discussion ensued about the institutional conditions for youth there.

The students also presented it to Satellite’s full student body, who gave us generally positive feedback and thought our version was realistic. After the Satellite school screening, the students returned to their classroom for their evaluation.

It would be many years before EVC began using evaluation rubrics and our signature process of portfolio assessment, but Liz and I had decided that the grading process should be shared by the students. We created a circle for discussion. I was struck by how direct and honest the students were. Each student reflected on their learning and participation, proposed the grade they had earned, and accepted the judgment of the larger group. Not only had we pulled down the wall between producer and audience, we had pulled down the wall between student and teacher.

I had aspired for this first class to be a documentary workshop, shaped by the limits of equipment and school-based conditions, and team-taught with an academic subject teacher. As it happened, it became the foundational model for what EVC later called our Professional Development Program. Over the next semesters, I taught more interview-based and vérité-style documentary classes, but still with a youth-centered goal of supporting the youth producers and youth audiences in a self-directed transformational experience. To underscore the transformative and participatory foundation of this method, I called the next Satellite class the “Living Television” workshop—an homage to the depression-era Works Progress Administration’s (WPA) and Federal Theater Project’s Living Newspaper, and the Latin American Living Theatre that had used interactive community theater for entertainment, education, and consciousness-raising. Over the years, student dramatizations and reenactments became a regular part of EVC documentaries.

The half-inch tapes for “Memories of Mandelay” haven’t survived the past four decades. My fragmented notes leave many questions unanswered. Yet, I’m struck by just how courageous the students in this first class were in investigating and expressing the often painful truths of their lives. And it's clear from my reflections that their dramatized story provoked critical discussion and questions about our students’ experiences that were too often hidden behind the walls of institutions, and unknown to most adults. In this sense, this experimental docudrama, shot with a shaky black and white camera and dim lights, gave expression to youth struggles and resilience amid institutional abuse and cut a path that later EVC students could build upon and use to flourish.

Comments